Following on from a previous post about how to improve the gaming experience. If I could choose one mechanic to remove from our pasttime it would be Quick Time Events.

If you have a moment, I’d like to make the case for why they’re a bad idea not only from a user experience perspective but also how they have a negative influence on gameplay and mood.

How it all started

Dragon’s Lair is widely regarded to have one of the first instances of Quick Time Events. With required button combinations needed to be pressed in order to aid Dirk the Daring to his goal – rescuing the voluptuous Princess Daphne. It was a revolutionary idea at the time, and one fit for an extraordinary game.

Fast forward over 25 years however and QTEs are in a vast array of games from an increasing amount of genres. What was once a new and exciting idea has become an gaming mainstay, and I believe it is quickly becoming an unwelcome one.

The timed button controls suited a game like Dragon’s Lair because it was born out of the arcade scene and this new method of control suited the environment of it’s conception. Quick bursts of play, with continuous repetition to reveal more of the game to overcome problems by trial and error, and in doing so allowing others to observe and win using collaborative observation and completion.

In this sense, this age-old use of the QTE has evolved into something else entirely, a secondary and more dangerous use, a ruse to help make the cinematic moments of games more interactive or a moment to increase the tension of a particular scene. Now its not just about controlling adventure games anymore but FPSs (Call of Duty 3’s one on one button mash) Action games (Resident Evil 5’s QTE filled cutscenes) and just about everything in between. The questions I keep asking myself is how long before every game genre makes use of them, and where will developers draw the line?

Why they don’t work

I believe QTE events take the player out of the experience of the game rather than immersing them further. Before QTEs you would instinctly follow a control scheme to complete a goal. With them you’re constantly following directions from the screen, and doing so isn’t fun like similar examples (such as rhythm action games) but tense affairs as you wait for the next moment of QTE to hit.

On a narrative level they often break the forth wall, distancing you from the story on the screen by reminding you you’re playing a game often doing the exact opposite of the intended purpose. Above all Quick Time Events promote reaction speed rather than honest skill. From a design perspective QTEs change the point of eye focus from the entirety of the cut scene to the position of the button flashes, the actual story is often pushed temporarily to the peripherary vision.

Ultimately when QTEs are failed they are a signal to the gamer that they are a failure, unable to prevent a negative outcome or in many cases the death of their character. If you mistime a jump in Tomb Raider due to a genuine mistake there is at least an element of logic and more importantly a way to improve. When Lara’s death occurs because of a flippant button press outside of your control it seems more unreasonable.

This creates a sticking point that are a distraction from the momentum of the rest of the game, and such quick failure turn around at the touch of the button increases the frustration of the regular gamer at worse, but they must be even more of a burden to more casual gamers, as they find it even more difficult to make rapid fire decisions between controller and screen.

The progression of QTE’s often follows the progress of the game – with more complicated and frequent patterns occurring nearer the end of a game. This means that they can frequently create spikes of difficulty as the QTE frequency becomes more difficult than the game itself. Even a game that uses them well struggles to find the balance between not enough and too many. If QTEs are made too rare within one game the difficulty often increases as the player struggles with each instance. If they’re too common, then the moment for the player to pause, relax and enjoy during the cutscene has gone entirely.

QTEs are frequently squeezed in to just about every part of a game. Any moments of gameplay are fair game, no moment is safe and its now become harder to take a break or put the controller down, particulary when paired with another gaming bugbear of mine – the inability to pause or skip cutscenes.

The alarming rise of Quick Time Events mean that in order to evolve the idea even more complicated button combinations have emerged including the “shake the controller to survive” scenario This leads to a watering down of what was initially quite a good idea – in moderation. The window of time in which “to succeed” becomes smaller, and varies with every game as mastering button combinations on one game will not protect you from another’s usage.

Come to think of it how many gamers do you know that actually enjoy the premise of QTEs? After all isn’t a game about enjoyment at the game of the day? When did something that so few people can actually properly engage with become not only commonplace but a practice that’s actively encouraged?

My reactions are pretty good, but I will often struggle with the most generic usage of the QTE, so it begs the question of who they are really serving, the gamer or the developer? That’s a tricky conclusion, but there are instances where Quick Time Events can work well.

Why they continue to be used

Ultimately QTEs are a way to force players to sit through cutscenes, this is backed up by the fact that a lot of QTE events often cannot be skipped – even if the player has previously played that area of the game.

They are also trying to address the criticism that certain games have become too cinematic with an overuse of FMVs with little or no gamer participation. I would argue that this is a potential arguement for more in-game cinematic sequences and skippable story.

And while I have been quite negative about QTEs so far, one of the advantages of them is they can assist the player by helping them to avoid tricky moments of combat or adding extra optional bonuses that wouldn’t have otherwise existed. Placing the buttons to press in game can be rewarding if ample warning if given, such as the modern Tomb Raiders use of grapple hook buttons on usable areas.

Quick Time Events primarily add a degree of spontaneity to games, a factor that mixes up gameplay while supposedly making things more exciting. I would argue that it does it doesn’t quite manage this, and leads to more annoying, unintended outcomes. If QTEs must continue to be used there are some best practice methods that I would urge development companies to follow.

How they can work

-

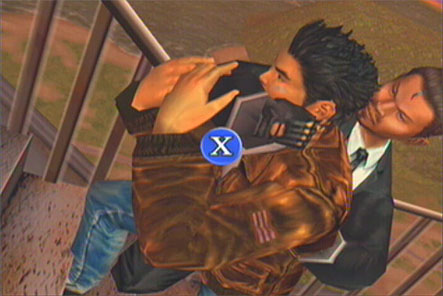

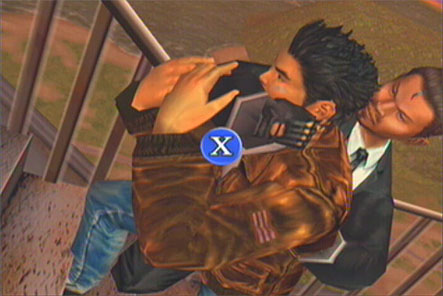

Allow players to avoid combat

QTEs are extremely useful for dodging tricky situations. At moments where combat or action is overwhelming they can be a brief moment of respite – but only if the QTEs are easier than what you were originally trying to avoid. The first Shenmue game balanced this perfectly, and as a result is widely regarded for popularising the concept.

-

Make them skippable as part of cutscenes

Often if a cutscene has QTEs in it then it becomes immediately unskippable. There are some notable exceptions; Resident Evil 5 would allow you to keep certain QTEs that have been played before, but others remain mandatory. Ultimately if a game has cutscenes that are skippable then the QTEs should be too, ideally there should be some logic in place on the retry portion of the QTE to determine that you’ve already completed a previous section and let you retry only the one you’re stuck on.

-

Use in moderation and in the proper context

Both of these points follow the other. QTE’s work in moderation if the action that you are performing matches the context of the game. It it in some instances logical for a button press to mean the avoidance of danger or an optional benefit, but QTEs will frequently be squeezed into any scenario. If you find yourself asking why you’re having to finish a QTE to do something then the designer has failed.

-

Simple button combinations

Ideally QTEs should remain a single button press or direction on the d-pad, at worst a combination of two buttons which are next to one another. Other actions such as shaking the controller should be avoided if at all possible

-

Bigger margins of error

This is a huge problem. There needs to be bigger and better time limits for the correct button combination to be entered. QTEs should be more forgiving in every instance giving gamers the best possible chance to succeed.

-

Make QTEs completely optional

If QTEs must continue to exist then hopefully more developers will acknowledge the annoyance surrounding their use and provide an option in-game to turn them off from the offset, this would allow the player to view the cutscenes as intended without disruption. Alternatively QTEs could be used for additional or optional content providing a rewards for those that tackle them.

So, in my perfect world we’d have a QTE amnesty, but I do appreciate there are games that do use this mechanic well. I’m just struggling to think of any at this point in time. Care to suggest any?